This article was published in the Sunday Herald on 22 October 2017.

“DAD, I’m going to tell it to you straight,” I said at the dinner table, aged 17 and ready to jump into the big wide world. My parents put down their cutlery in preparation for whatever was to come. “I’m not going to do Celtic Studies,” I blurted out, and I remember their faces still, choking on their sprouts in their efforts to hide their amusement.

Celtic Studies was my father’s all-consuming passion, and 16 years after his early retirement from Edinburgh University, it still is. We have no family connections to the Highlands and Islands – growing up in a house in Glasgow full of French, English and Italian (and a smattering of Arabic), my father took an interest in the Gaelic he heard about him in the trams and streets and classrooms of the city.

“There were so many Gaelic speakers among my teachers,” he wrote about his time at Glasgow High, “that you could have done a statistically-viable social survey on them … The head of English was president of the Glasgow Islay Association. When I put some Gaelic in an essay he perked up, summoned me to his desk and asked what dialect I spoke.”

“I found that strange,” he wrote. “Here was something as fundamental to the fabric of our nation as anything I could think of, yet which my school regarded not as a subject to be taught, but as something which you had or you hadn’t, like a dimple or ears that stuck out. Even a head of English hadn’t twigged that I had got it out of a book. I had stumbled across the plight of minority languages in the modern world.”

Thanks to the enlightened policies of Glasgow Corporation Education Department, my father was offered the chance to study Gaelic, and it became his life’s work. While many other families were losing their native tongue, he introduced it into ours. From the day I was born, he has spoken Gaelic to me, a gift I failed to appreciate at the age of five when I went to school in Edinburgh, where we lived, and started replying to him in English. But Dad persevered without a fuss until the time came, in my 20s, when I switched back to Gaelic, by now a clumsy mix of native intuition and assorted learner’s oddities.

And so I have stumbled through the decades, fiercely proud of my father tongue, but acutely aware of my linguistic inadequacies. An Edinburgh Gael, I always felt I should have some sort of innate knowledge of peat-cutting and the call of the corncrake, but these were not the world of my Gaelic. And now here I am in the Netherlands, deeply pained to have failed to pass it on to my own children, for whom Dutch has become their day to day tongue and English their minority language. I seem to be moving farther and farther away from source.

And yet, despite all that, here I am, publishing a book bang in the middle of my father’s field. So much for the great dinnertime bombshell. Celtic Studies has found me.

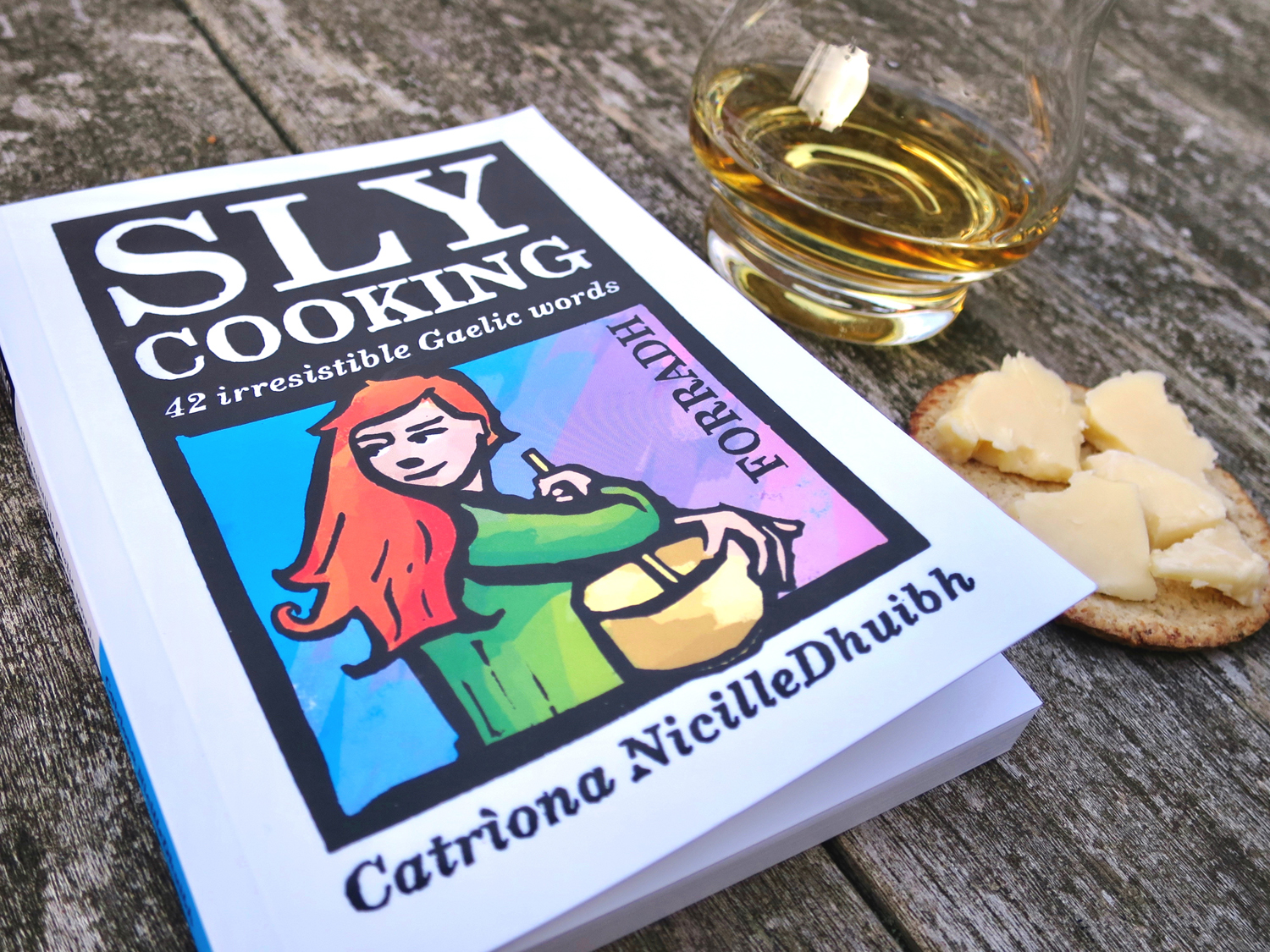

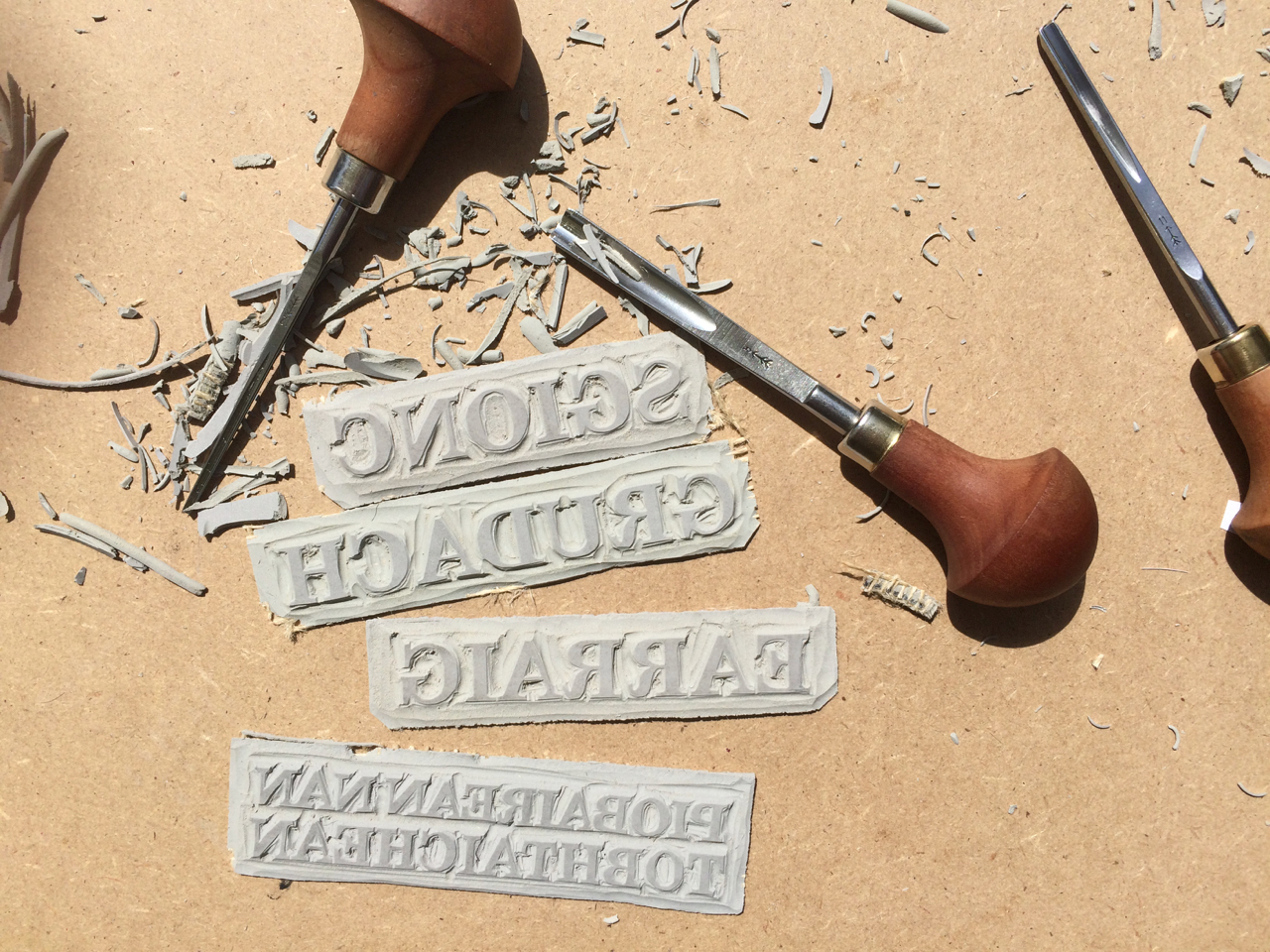

Sly Cooking: 42 Irresistible Gaelic Words is my tribute to a treasure trove of hidden linguistic delights. It’s a light-hearted illustrated pocketbook designed to bring a smile to the faces of Gaelic speakers and non-speakers alike. Who knew there was a word (forradh) for someone caught cooking something on the sly? Or for forcing something big into a hole too small for it (sgionc)?

Father Allan MacDonald knew, and thank goodness he wrote it down. A vigorous, charming, and famously tall young priest in South Uist and Eriskay from 1884 to 1905, Fr Allan was intrigued by the vast store of Gaelic stories, songs, superstitions and linguistic gems alive in the minds of his parishioners. Despite his gruelling workload, he found the time to take it all down in 10 big notebooks.

Fast forward to 1958, and Celtic scholar John Lorne Campbell extracted nearly 3000 words from Fr Allan’s notebooks to produce Gaelic Words And Expressions From South Uist And Eriskay, a dictionary so entertaining that you can happily read it from cover to cover.

That’s exactly what I did, five years ago, and it wouldn’t let me go. How could there be so many delightful words specific to such a small geographical area, and have they survived? It was like walking into a museum and seeing 3,000 stuffed animals I never knew existed, with powers and colours and plumes unimaginable, and not knowing which ones have become extinct, and which are still living and singing, and rearing their young in the world beyond these walls.

I love the humour which runs through the dictionary. There’s a real sense of human interaction and an ever-present gentle mockery which is still part and parcel of the culture. You might be bileagach (said of a person who must taste and sip every food or drink she sees) or maybe you do the opposite, a’ storradh food on people whether they like it or not. Perhaps you have a riobag shonais (hair of good fortune) growing on your chin, or is it a riobag chonais, the hair of quarrelsomeness?

I love the attention to small details and to tiny, almost imperceptible nuances: my favourite word of all is mionagadanan, the atoms seen in a ray of sunlight coming into a house, and equally beautiful is rong, the spark of life in a dying beast. The words tip over into the otherworld too, in a concrete, matter of fact way typical of Gaelic culture. If you wake up with mystery bruises, might you have suffered bìdeag an duine mhairbh, the dead man’s nip, perhaps from your husband’s jealous late wife?

I fell in love with these words, and despite my efforts to integrate into my new home of the Netherlands, to move on and let go of the past, Gaelic would not let me do it. The words were just too good, and Fr Allan’s story too inspiring. I set out to make illustrations celebrating my favourites, and my digital project grew arms and legs, ending up as 42 linocut prints, painstakingly cut and hand-printed in my freezing cold shed with cups of tea and Radio nan Gaidheal to keep me warm. An exhibition of these prints will be launched along with my book on Saturday (October 28) at An Lanntair in Stornoway.

I’m by no means the first person to be inspired by Fr Allan and his collections. During his time in Eriskay, the handsome priest became something of a magnet for curious ladies and literary celebrities from all over the world, subsequently popping up thinly disguised in novels, and written about with gushing admiration elsewhere.

And here I am, doing the same. I have to admit I’m one of his groupies. The “high priest” was devoted to his people, walking for miles on end to care for them in the harshest of weathers, lobbying the authorities on their behalf, and never losing his love for their stories. He suffered burnout in 1892, and instead of taking an easier gig in the city (the Bishop offered him a mainland town parish “with better living and the company of book-learned men”), he insisted on building a church in Eriskay and staying with his people there. Eleven years into his mission on the island, he died at the age of 45. “Father Allan went to his long rest,” said the Herald obituary at the time, “amid the tears of strong men not used to weeping.”

Like one of his Victorian lady admirers, I travelled to Eriskay and South Uist in May this year to find out if the words in my book were still remembered. My journey was filmed for a BBC Alba documentary, Mgr Ailein agus na Faclan (Fr Allan And The Words), to be aired on Monday, October 30. I felt embarrassed, knocking on doors with my list of words and my never-properly-fixed Gaelic, which jarred horribly with the beautiful, fluent speech of the locals I met.

But I had been empowered by Fr Allan’s personal diary. The man himself had struggled with his own perceived linguistic inadequacy as an incomer from Fort William, “confined from dawn till dusk in an English school … while the language which was most expressive and most natural to us was forbidden”.

“But how I envy the people who can speak fluent, well-pronounced Gaelic,” he lamented (in fluent Gaelic). “I can’t. In spite of diligence, youthful practice is better … I will never be completely at ease in Gaelic, and though I hate it with heart and with spleen, my Gaelic will always have the harsh stammering unpleasant accent of the English speaker which a tongue-tied, limping, stiff-worded English education has left in my head.”

What if Fr Allan had decided his Gaelic was not up to the task of collecting all the wonderful material he wrote in his “big book of yarns”? That he was wasting his time indulging himself (a fear which he did express) and should give up the indolence at once? We might be 3,000 words poorer now. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

So I gave myself a good talking to, and knocked on those doors, and the men and women I met were kind to me. What’s more, the words – about 20 out of my list of 50 – became real. I had found many of them alive after all, some tripping off the tongue in everyday speech and others hauled from the darkest recesses, breathing fresh air for the first time in years.

It was absolutely worth it. I gathered what I learned and am putting it all on a website to go with the book, slycooking.com. I might have dodgy lenition and extreme genitive confusion, but I am doing my little bit to defend a vast store of cultural treasure too rich and deep to comprehend.

How anyone can be against that is a mystery to me. Why do I still, in the 21st century, read in letters pages and newspaper headlines that money should not be wasted on Gaelic because it is nothing more than a costly distraction? Because it “was never spoken here”, a monstrously inaccurate claim in most parts of Scotland, especially the last time I heard it with reference to Moray? Why is East Renfrewshire doing its best to crush the ambitions of 49 families to see their children learn Gaelic, by rejecting their legitimate bid for primary eduction in the language despite the provisions of the 2016 Education Act?

My Gaelic is from Edinburgh. My father’s from Glasgow. The Scottish Parliament’s Gaelic officer is from Stepps and speaks fantastic Gaelic – with a pure dead strong Stepps accent by the way. It’s not enough to leave it to the good folk of the Western Isles to carry the torch – just the other week, numbers showed a distressing decline in children choosing to study the language there. Gaelic belongs to all of us and if we in Scotland don’t get behind it, who is left to care for all those beautiful endangered words, and the stories and genealogies and poetry carried along by them?

It’s been a difficult couple of months for the Gaelic world. The multi-talented, sparkling but troubled funny man Norman Maclean from Glasgow and South Uist left us at the age of 80. Accomplished and warm-hearted John Alick MacPherson, of North Uist and Cape Breton, left us on the very same day. And the premature loss, just three weeks ago, of joyful and talented Lewis screenwriter Chrisella Ross has hurt us all.

These people, Gaels through and through, were champions for the language in its most natural and life-affirming form. The loss of each one of them makes an enormous hole in Gaelic’s resilience. According to the census there are 57,375 Gaelic speakers in Scotland. That’s fewer than the number of words in the language. Having devoted the past few years to just a few of these words, I have become keenly aware that every individual Gaelic-speaker, whether native, a learner, at home or abroad, is precious and indispensable.

Now, more than ever, I feel a personal responsibility to step up, put the work in, bask in all the beautiful expressions I can find and share them with my children. To be one more defender of the treasure, and not one less. Because Gaelic needs every one of us, and what beautiful gems it has to offer in return.

Sly Cooking: 42 Irresistible Gaelic Words, £5.95, Acair

Mgr Ailein agus na Faclan, BBC Alba 9pm, October 30, 2017

_______________________________________________________

About Catriona

About Catriona

I love to tell stories. My career has covered many bases, but communication has always been at the heart of everything I do. From journalism, politics and PR to art and design; from broadcast animation to published picture books and copy editing, it’s all about making people look and listen, and love what they hear.

Looking for a copywriter to help you tell your story? Get in touch!